Currently, the UK is facing difficulties in its supply of STEM-skilled workers — that is, workers who are trained in science, technology, engineering, and maths subjects. One report has highlighted just how much this is impacting the nation's economy, with an estimated £1.5 billion cost attributed to the UK's lack of STEM workers.

Many solutions are being explored, but one with the most promise appears to be apprenticeships. As apprenticeships offer a more hands-on approach to subjects, they work particularly well for STEM subjects. With this in mind, how can employers and companies ensure that STEM-based apprenticeships are appealing?

Electric motor rewind specialist Houghton International explains how it sees things...

The UK's STEM skill shortage

It's important to understand the extent of the UK's STEM skill shortage and its potential impact in future. According to a response by the Royal Academy of Engineering, more than half of engineering companies say they have had problems recruiting the experienced engineers they need. This demand for skilled and experienced engineers is set to increase considerably over the next three to five years — 90% of engineering, science and hi-tech businesses expect this to be the case. But what is causing this gap?

For STEM-centric businesses, an ageing workforce is also a concern. As skilled and experienced engineers retire, it is increasing vacancies across thousands of engineering roles. Putting a more exact figure on this is EngineeringUK, which — through detailed analysis — has determined that there are annually 29,000 too few workers with level 3 skills and an even greater shortage of more qualified engineers — 40,000 of those with level 4 and above skills.

Of course, as with all industries, Brexit is also playing a part in this problem. As uncertainty remains, the UK’s exit from the European Union could create an even bigger headache for those in STEM sectors.

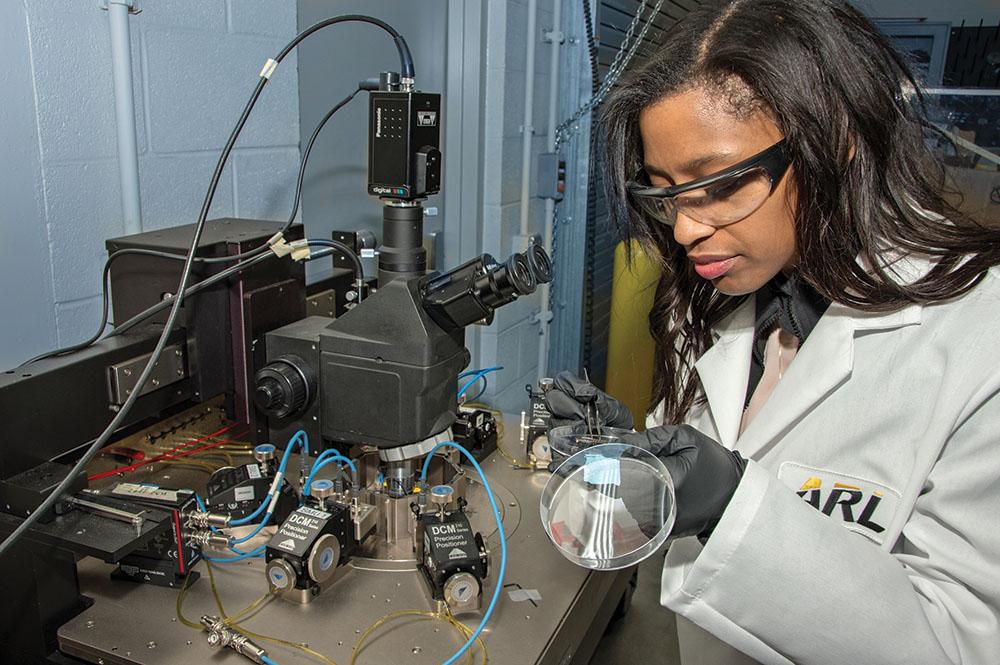

Diversity is a key action point for businesses looking to close the STEM skills gap. At present, under 10% of the engineering workforce is female, while those from minority ethnic backgrounds make up just 6% of the workforce.

BACK TO ENGINEERING CAPACITY NEWS PAGE

Are apprenticeships the much-needed answer to the STEM shortage conundrum then? Apprentices in the UK

Long gone are the days of finishing school and heading straight to work. Nowadays, students have a wealth of opportunities to choose from, whether it’s A-levels, BTECs or apprenticeships — and the latter is growing in popularity. In the 2016-2017 academic year, 491,300 people started an apprenticeship, with almost a quarter of those under the age of 19. Each month, an average of 23,000 apprenticeship opportunities are listed on the government’s Find an Apprenticeship site, while organisations — such as WISE, which campaigns for gender balance in science, technology and engineering — are continually driving initiatives to help grow the number of apprentices in these sectors.

Michael Mitten, CEO of Houghton International, spoke on the issue: “Apprenticeships have been an important part of our business since it first started over 30 years ago and I firmly believe they have been key to our growth throughout this time. As we expand further, our continued investment in apprenticeships is fundamental to ensuring we can maintain a skilled workforce for years to come.”

But according to the Financial Times, the scheme may well be suffering its own issues. Between May and July 2017, parliamentary statistics show that only 43,600 people began an apprenticeship, which is a 61% reduction from the 113,000 that started in the same period in 2016. This has been largely accredited to an apprenticeship levy that was introduced in April 2017, which every employer with a pay bill of more than £3 million a year must adhere to if they want to employ apprentices.

Has the level of apprentices dropped for engineering and related areas though? Apparently not. In 2016/17, 112,000 people started a STEM apprenticeship — up from 95,000 in 2012/13. This growth is impressive and may be a sign that STEM employers are taking on board the warning that they must be creative with their recruitment processes.

Former director of the Apprenticeship Ambassadors Network, Rod Kenyon, noted that: “The traditional recruitment pool is diminishing at the same time as work-based learning routes are facing increasing competition from alternative post-16-year-old provision. Employers wishing to attract quality applicants in sufficient numbers to meet their skills requirements have to look beyond their traditional sources.”

STEM employers may well be neglecting certain demographics that could potentially address the skills gap too. Overall, women account for 50% of all apprentices in the UK. However, for STEM apprenticeships, they make up just 8%. STEM employers are overlooking a great talent pool if they don’t concentrate on encouraging women into their companies. According to WISE, 5,080 women achieved a Core-STEM apprenticeship in 2016/2017, while 62,060 men accomplished the same in the same period. What makes this statistic even more concerning is that, according to an Apprenticeships in England report published by the House of Commons Library, 54% of overall apprenticeships starts were women in 2016/2017. Evidently, women are opting for apprenticeships in different fields, which means that STEM industries will continue to miss out on thousands of potential workers until the popularity of STEM careers increases amongst women.

STEM apprenticeship improvements

By 2020, the government aims to have three million apprenticeships commencing. So does this mean we can expect more initiatives that encourage programmes like these in all sectors, including engineering? Possibly, but more work must be done to hit this lofty figure.

Careers in STEM industries must be presented positively at school in order to encourage young people to pursue a career path in that direction. Career advisors should make it clearer to kids that a university degree is not the only avenue to success and that the same level of fulfilment and opportunity is available with STEM apprenticeship programmes. Perhaps this means a stronger relationship between STEM firms and educational establishments, which can grant more opportunities for schoolchildren to get first-hand experience of how these companies work in practice prior to having to make an official decision.

Of course, incentives can be a motivator too. Already, the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) offers around £1 million in prizes, scholarships and awards — including the Apprentice of the Year Award — to recognise successful people in its industry, which acts as a great incentive for young workers to enter the sector.

While apprenticeships could definitely help reduce the pressure of STEM skill shortages and an ageing workforce, the schemes need to be presented as a viable and equally-valuable alternative to academic paths.